This is the second part in a 3-part blog series. Read the first blog here.

The lies began unraveling as I found myself in my first full-time “white collar” job, working in an upscale retail store in my hometown of Jackson, Mississippi. My two managers were Mary, and her assistant, Paul. They were Black, and they were excellent.

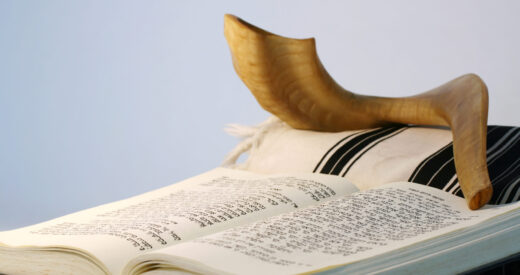

Growing up in Mississippi in the 70s and 80s, I was immersed in a culture of insidious narratives about other cultures, mixed delicately with family values, strong work ethic, and Southern hospitality. These lies were based on the nobility of White people and how they somehow managed to build a successful society for themselves despite having a Black population of nearly 40 percent, the highest in the country.

Some of the concepts that supported White supremacy seemed to be as ubiquitous as the humid air we breathed, while others were explicitly taught in schools. Either way, I must balance in my mind—and it is a balancing act—that these were the people and this was the place that instilled in me much of what I am proud of as well. Not to absolve anyone of any level of responsibility, but it reminds me that so much of what we do and what we learn in society goes unchallenged, whether for its relevance or its truth. But through a process of awakening, as I’m chronicling here, many of us have questioned what was handed down to us. The tough part of that balancing act is to treat people with grace and forgiveness, which seems to be a better path to truth and reconciliation for all.

Nonetheless, a belief that Black people were “less than” was pervasive where I grew up. Another prominent narrative explained away Black authors, athletes, and TV and film stars as the “good ones” or exceptional. As for what we were taught in schools, let’s just say that Mississippi’s Jefferson Davis, who led the insurrectionist government during the Civil War, was portrayed as heroic, or Confederate generals like Thomas “Stonewall” and Nathan Bedford Forrest (the latter being the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan as well). Conversely, any discussion of Martin Luther King, Jr. was reserved for Black History Month, which came about while I was in elementary school. Meanwhile, Medgar Evers, a civil rights activist murdered by a sniper, in his home and in front of his family, about two miles from where I grew up, never merited a mention. Neither did Emmitt Till, nor scores of others who marched, suffered beatings, or died for the cause of civil rights.

Instead, we celebrated unrepentant racists like Governor Ross Barnett, who personally sought to prevent James Meredith’s entry as the first Black student at Ole Miss. As Barnett and other leaders rallied whites against the tensions of the Civil Rights movement, so began the decades-long tradition of turning Ole Miss football games into a sea of Confederate battle flags. I cherished mine growing up, and in fact, the only decor I bothered to install in my college dorm room as a first-year student was a battle flag that spanned the entire width and height of our window.

The lies captured our imaginations through every converging force a child faces growing up. Our families, friends, teachers, church leaders, coworkers–unconsciously or not–all had a role in perpetuating a caste system so that, years later when I studied apartheid South Africa, I thought I might as well have grown up there.

The lies had been told so often and so thoroughly that, most of the time, they didn’t need to be told any more. When virtually everyone in your social group believes a lie, there comes a time when it doesn’t bear repeating. The lies of the Lost Cause had saturated our social consciousness. By the time my generation came of age, White supremacy was mostly unconscious, yet still quite strong.

How does the big lie remain entrenched in many ways, still today? Here’s an interesting example of what a warped society teaches its children. In our American and Mississippi history courses, typically taught in eighth grade (American), ninth grade (Mississippi), and eleventh grade (American, again), we would study the buildup to the Civil War, the war itself, and its aftermath.

In a less White-centric approach, one might not be taught of John C. Calhoun and his courage to offer nullification as a way to preserve slavery in the American South. You might not be taught that Robert E. Lee was the greatest military tactician of his era, while the guy who actually won the war and later served as President, Ulysses Grant, won the war in spite of himself. And you certainly wouldn’t have been taught that the Whites who moved to the South, referred to jeeringly as carpetbaggers, were only eclipsed in their Reconstruction-era loathsomeness by the so-called scalawags, those who betrayed their fellow citizens by working with the US government in its failed attempt to reform the apartheid South.

I don’t want you to absolve me of anything, but you can definitely understand how I, a 19-year old who had earned nothing in life, felt entitled enough to look down on Mary and Paul before I’d ever met them. I was locked and loaded with resentment, fed a steady diet of superiority my whole life. My privilege was off the charts.

With Mary and Paul, I expected the worst. I certainly didn’t expect any grace. From my experience, White men almost never worked for Black people, so I would have figured that Mary and Paul could be in their positions due to affirmative action policies or just because they were two of the “good ones.”

There on the sales floor of the Gayfers Department Store at Jackson’s Metrocenter Mall, Mary and Paul were gracious, affectionate, and nurturing. The three of us became friends quickly and earnestly, without suspicion. While I saw Mary as one of my early mentors, I saw Paul as a cool older brother. Mostly, I saw them for who they were–bright, kind-hearted people in spite of it all. They’d endured the same upbringing I had. Yet they were resilient rather than resentful. We talked a lot about what their world was like, in contrast to mine, even though these “worlds” were just a few miles apart.

Even though I had gone to public schools for most of my education to that point, sharing classrooms with Black children along the way, I was enlightened to the Black experience of that time mostly through these two colleagues. There was a feeling of sadness that I developed when sharing shifts with these two, as I wondered how far they could really go in their careers. I had very few models, at that time, that would predict an open path for success for either of them. I myself, in contrast, had tried as hard as I could to squander opportunities I had earned and which had been presented to me because of my privilege. And yet, my privilege allowed me to rebound over and over again as I walked a wayward path into my twenties.

I didn’t become anti-racist overnight, but something in me had shifted, and the spark of radical change certainly lit around that time. Once your mind is opened for the first time there’s no telling where you’re going to uncover the truth next, burying yesterday’s lies. There are some strong indications that many of my fellow Mississippians feel the same way and have walked the journey I have in life, as evidenced by last year’s triumphant removal of the Confederate battle flag from the state flag. The state’s new flag features a distinct, enduring symbol of beauty and unity, the magnolia, and while Black legislators led the fight for decades, their White counterparts joined forces to make it happen in 2020.

My time with Mary and Paul was a time I like to think of as first gaining my sight, of finally seeing many things that were right in front of me my whole life. But I couldn’t see everything yet. Just a couple of years later, I’d find myself living nearly 600 miles to the northeast, and it would seem like light years away from the customs and values I’d grown up with in Mississippi. The next leg of my journey of awakening would take me into the world of the LGBTQ+ community, something I’d never openly encountered.

Read the third part of this blog series here.

Brian Castle is the Founder & CEO of Parklife Communications, a full-service content shop serving small and mid-sized companies and larger agencies with a digital marketing focus. Brian is passionate about collaborating with executives and entrepreneurs to help tell their stories to effect positive change.